The parallels of working on cars and software - Part II

This is the part two of my series on the parallels of working in cars and software. You can find Part I in the archive.

In this part I’ll cover some aspects that, for me, are not obvious at first. Almost all of the ideas I’ll list here were revelations that came to me with time - some actually only came to me after I stated writing this series.

Methodical

According to the MacOSX dictionary on my computer, “method” means: “a particular form of procedure for accomplishing or approaching something, especially a systematic or established one”. To work on cars, one has to be extremely methodical. This means following a step-by-step procedure to tighten screws, nuts and bolts; to change the oil; to drop an engine; install the bearings; how to align a screw. All of these and many others have to be performed extremely carefully and with attention to detail so that they are accomplished correctly. It is very easy to mess something up. Sometimes it can be even a bit boring how much method you have to follow.

While working on the engine, I was automatically engulfed by any activity that we were performing. From the simply tightening screws in the engine tin to assembling the cylinder heads. These took all of my attention and focus not only because I enjoyed what I was doing, but because that was required in order to do it correctly. Any simple mistake could hinder the performance of the engine in the best case or cause complete failure in the worst. On top of that, one can rarely parallelize the tasks performed while working on a car.

I always dedicated all of my attention to what I was doing to the point that I rarely thought about looking at my phone, listening to music or any other common form of distraction/parallelism that we’re used to on our day to day. Most of the time, even the conversation with Jim had to stop so that we both gave our undivided attention to a task.

For me, the world of software is not very different. While working on a piece of software with my undivided attention always yields the best results. Undivided attention means turning off my cellphone, instant messaging, email etc. These take my brain power off of the task at hand and impact my output. Additionally, for more manual and repetitive tasks, I add another layer to the task: write down a detailed step by step of what I need to do so that I can just follow it instead of coming up with something as I go. This usually frees up my mind to perform the step itself rather than what I need to do next. Being extremely methodical is a way of guaranteeing consistent results.

Some people aren’t so strict and can perform really well while listening to music, answering instant messages or being distracted by other things. That is not how it works for me. I perform a lot better (in terms of quality of the output) when I am able to get into a flow state where I’m completely immersed in a task at hand.

This is perhaps one of the most controversial lessons of this whole series as the shift from parallelization usually instantly leads to the perception of lower throughput of work. I strongly disagree with that. It may seem like the case at first, but a single thread of mental activity usually leads to higher quality and faster work, which, by definition creates more capacity and more importantly, it generates less bugs (and, consequentially, re-work).

Unit and integration tests

A mechanic performs almost as many tests as a software engineer on their day to day. These tests vary from a single unit of the engine, to the interactions of two units and the whole operation of the system. During our rebuild, Jim and I had to measure weight of the pistons to make sure that all four were within five grams of each other; we had to measure the thickness of the shims for the crankshaft; the endplay of the crankshaft + flywheel and many other things. As we moved along in the rebuild, the checks for correct operation of each one of these parts gave us more confidence that the whole system would work correctly. We could have skipped some of these tests to save time, but a badly configured endplay could jeopardize the operation of the engine under certain circumstances and that was not a risk we were willing to take. We needed the best coverage we could get with the tools and time available to us.

I hope that the parallel to the world of software is obvious on this one. We need to test our components individually (unit tests - the same way we measure the weight of the pistons), test the operation of two or more components combined (integration tests - the endplay check which involved the crankshaft, flywheel and its shims) and that the whole system connected works (smoke test - more on that below). The existence of each of these different types of tests has a different “responsibility” in our day to day. If we don’t have confidence that the units that comprise the system aren’t working individually, how can we have confidence and ascertain the correctness of the whole system or parts it?

The goal behind all of this work is to be sure, with the highest degree of confidence that is possible in terms of cost benefit, that what we’re doing is going to work well (or at least according to the specification). There is no point in doing work without making sure the pieces are doing what they are supposed to do. The way I see, tests are an essential part of the work, not extra.

Research

There were times during our rebuild when we didn’t know how to proceed. That often happened because the problem was not mentioned in any of the manuals we were using. In these moments, we had two common avenues: we’d research in online forums or we’d call a mechanic with experience in the Type IV engine to ask for help. One way or another, we always got to an answer (for example, when we didn’t know how to properly and safely remove the pilot bearing).

The same happens in software: we are constantly facing new problems, bugs, investigations. We often have to do our own research (in literature, online, internal manuals etc) and when stuck, rely on others to provide assistance or even act as a rubber duck. Research teaches us new things and can give us confidence in our judgment. At the very least, it provides us with new ideas.

Smoke tests

Once all parts were assembled, the engine was oiled up and in the car, the next step was to fire it up. For Jim and I, this was both a scary and exciting moment. After months of work, everything was in place and ready to go. It was a matter of turning on the key. As exciting as that was, we had to do it safely. Therefore, for the first time we turned the engine on, we did so in a controlled environment: my in-laws garage. It is isolated from all of the other cars (and people) so that we didn’t cause any harm while giving us plenty of room to observe it in use. The idea was to fire it up and let it run in idle in the garage for 15 minutes so that we made sure there were no leaks (of oil, exhaust, gasoline etc.) and that everything was working smoothly. It was quite literally, a smoke test.

In software, smoke tests are a way of making sure the very basic functionalities of the system are working well (the concept of smoke tests actually comes from electronics - hence the name). Not many features are tested in depth, but only the bare minimum that are required for the software to be considered operational. These tests can be automated in a test environment or using a test instance of the system brought up just for this purpose.

In the engine smoke test, we didn’t test for gasoline consumption, oil pressure, temperature, performance at different speeds etc. We just made sure that it turned on and idled fine. The more complete tests would happen later in the process. Similarly, in a software smoke test, one wouldn’t usually test for performance, vulnerabilities etc. focusing mostly on whether the system is coming up well and able to perform some tasks. Although it may seem that this doesn’t add much value, it is a stepping stone to more elaborate exploration done later.

Alpha environment

During the rebuild, there were a few delicate steps that, if done wrongly, were going to be extremely hard or time consuming to undo. Dropping the distributor shaft was one of them. The distributor shaft is a piece of metal that, in the bottom part, connects to one of the gears in the crankshaft and in the top connects to the bottom of the distributor. It lives inside the crankcase and it is essential that it is properly in place otherwise the engine will misfire badly. Jim and I were very afraid to mess up this step. An error here would only be detected once we fired up the engine (which meant that we would have put everything back together and in the car again).

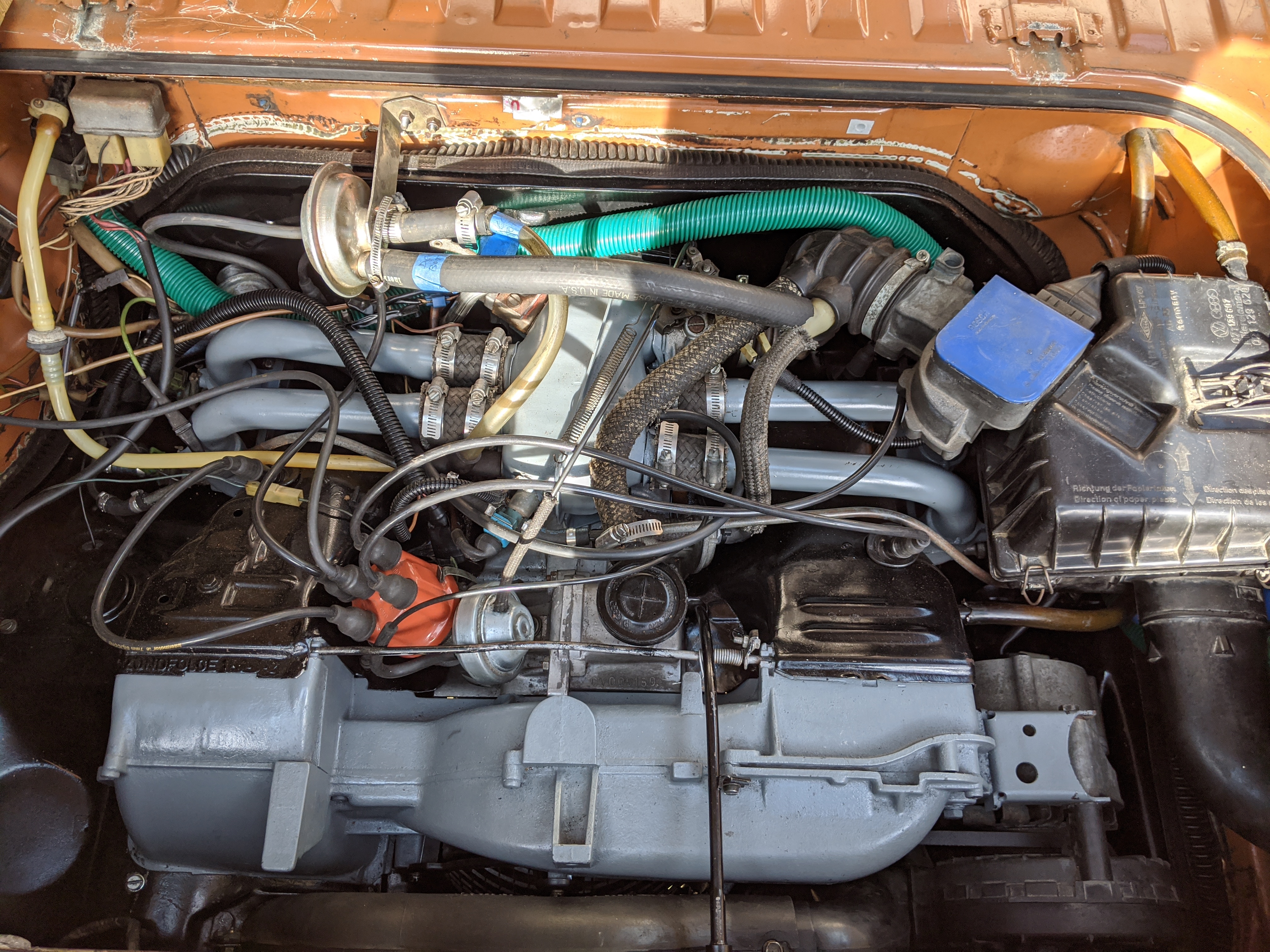

The engine in the car (in the garage)

The engine in the car (in the garage)

Luckily, we had another engine lying around! Since we weren’t doing the work on the engine that we pulled out of the car (remember that I bought an extra engine?), we could practice the process in this spare engine to make sure we got it right. That is exactly what we did. Being able to practice and test our procedure in a test engine, gave us confidence that we knew what to do when we got the new engine.

This can happen mostly (if not all) of the time in the software world. We can (I’d dare say should) practice most procedures in testing environments to make sure that they work correctly. These procedures can be: database migrations, UX changes, feature flags etc. Most importantly, the software itself should be used in testing environments (preferably by more than one person) before going live. Doing so regularly will reduce the number of bugs that make it production as it is used in ways that resemble production.

Debugging

Even when mechanics do everything right and according to the manuals, things can still go wrong. Jim and I had followed the many step by step procedures thoroughly and didn’t miss anything. Yet, during the first time that we tried to fire the engine, it didn’t start. A detailed observation and troubleshooting followed. To understand what was causing the issue, we had to observe the system. We had to get as much information as possible in order to devise a strategy to fix it. We came up with a few questions that would help us: Was the timing adjusted? Was the ignition firing? Was the engine turning? Was the coil getting current? Were the smart plugs connected? Were the spark plugs getting current? Does a visual inspection of the whole system show anything wrong?. When we successfully answered one of those, we moved one step closer to finding the component that was at fault. Once we found that component, we’d follow the specified manual procedures to either fix the component or replace it completely.

We used a timing light to see if the spark plus were getting current and it showed that they weren’t. That discovery let us narrow down the issue to the electrical system and upon close inspection of the connections and the wires I realized that one of the wires to the distributor hall sensor was broken. That explained why the engine turned, but not fired and why the spark plugs weren’t firing. We promptly soldered the wire and the engine started! It sounded and worked beautifully after that fix. In my day to day investigating bugs, I often follow a similar process. Whenever an issue is reported (either by a user or automatically) on a system, I narrow down the possible location of the issue by looking at metrics, logs, reports etc. Using all of the data available (or gathering new data if it is not), is the only way that I can properly find the cause for a problem. I cannot just out of thin air come up with a theory of what is wrong. I have to look at the clues available.

Unlike the world of software, however, in cars I cannot create an automated test to verify the fix for my problem. If a problem happens again, I have to start the troubleshooting procedures from scratch to determine the root cause. In this sense, software engineers are luckier than mechanics.

Escalating to another team

The last parallel that I want to bring up is escalations. After firing up the engine, Jim and I noted an oil leak coming from one of the oil galleys that the machinist had worked on. This was a piece of the crankcase that he had drilled and tapped to avoid a problem that happens on these old engines during cold weather when the old galley plug just shoots out of the crankcase if you’re curious. This leak was due to the plug that he had used - it didn’t seal the hole well, so not only oil was leaking through but also the oil pressure was dropping at times. This was bad and extremely frustrating news, because it delayed the completion of the project and it was not caused by something that we did wrong. After allowing ourselves sometime to complain and be angry about it, we set out to fix it.

Our first line of action was to try to fix the plug ourselves. We debated the problem and researched our options. In the end, I bought a couple of new plugs and we tried them with no luck - the leak still happened. Next step was calling the machinist, since he had worked on the galleys. He suggested using epoxy around the plug in order to seal the hole - we tried that and no luck as well. With all of our own options exhausted, we took the car back to the machine shop where they took the engine out and fixed the issue themselves as part of their warranty for having initially worked on that part of the engine.

In software, we tackle hard problems all of the time. A lot of the times, problems that weren’t caused or created by us. Sometimes solving these issues are beyond our knowledge or abilities and we need to call for help. This can be frustrating, especially after spending so much time and effort on an issue, but ultimately the proper operation of the system is the goal. Although admitting that I cannot (or don’t know how to) do something is not always the most fun thing to do, I see that as an opportunity to learn from someone with more knowledge than me. Voicing my own ignorance opens many more possibilities for me as it frees me to learn.

—

I hope that you’ve enjoyed the comparisons between working on cars and the world of software.

After finishing the engine and some other minor improvements on the car, I sold it. It was never my goal to sell the car when I started the project, but after it was back with me I realized that I didn’t like driving stick shift anymore (I had my fair share of it already in my life). I sold it in 2020 and got a newer Vanagon version with an automatic transmission. Now I don’t need to shift gears anymore.